Jumping to a solution? Why it is part of the process

It’s simply how designers think.

🕰️ Est. reading time: 4 minutes

Do you find yourself, as a designer, instinctively coming up with ideas when you’re supposed to be discussing and understanding a problem?

You quickly start imagining potential solutions, even when many things are still ambiguous.

You might even feel guilty for jumping straight to solutions.

Jumping to a solution isn’t necessarily the wrong move.

Join 1k+ readers and get my next post straight to your inbox!

If you’re enjoying the content, consider donating as little as $5 to treat me to a ☕️ coffee—it helps fuel more great ideas. Thank you!

Nigel Cross, a professor widely recognized for his contributions to design research and education, found that designers often jump to solutions (or partial solutions) before fully formulating the problem.

Designers are more solution-led rather than problem-led.

They make guesses and focus more on solutions because their primary goal is to develop a design proposal, rather than to conduct a thorough problem analysis.

“Guessing” is a part of the design process

Or, if you prefer, you can call it an ‘educated guess’ or ‘hypothesizing’ to make it sound less like a gamble.

It’s not random speculation—it’s based on knowledge, experience, and the available evidence.

This way of reasoning is integral to how designers approach problems, known as abductive reasoning.

Abductive reasoning occurs when you don’t have all the information. You take what you do know, come up with a likely solution, and test it. As you gather more insights, you adjust and refine your approach continuously.

In contrast, deductive reasoning guarantees a true conclusion if the premises are true. For example: All humans need water to survive. John is a human. Therefore, John needs water to survive.

Inductive reasoning works by generalizing from specific examples. For instance: Every time I water this plant, it grows. Therefore, watering the plant makes it grow.

Meanwhile, abductive reasoning focuses on forming a hypothesis that makes sense—a plausible hypothesis. This hypothesis is a reasonable assumption based on the best available information, which you refine through testing and learning as more details come to light.

Plausible hypothesis in general context

Imagine you come home and notice a strange smell in the kitchen. Based on your experience, you make an educated guess (a plausible hypothesis) that the smell might be from food left in the fridge for too long. However, you know there could be other explanations, like something burning in the oven or a spill that hasn’t been cleaned.

To figure out the cause, you start checking the fridge, the oven, and other areas to narrow it down. The initial guess about the spoiled food was a plausible hypothesis—it made sense given the situation, but you needed to investigate further to confirm it.

Plausible hypothesis in product design context

Let’s say you notice that users are spending a lot of time on the payment screen but not completing their bookings. Your plausible hypothesis could be that the payment process is too confusing or has too many steps, causing users to abandon their bookings.Based on this hypothesis, you might design a simpler, streamlined payment process. Next, you would need to test it by gathering feedback or tracking whether more users complete their bookings after the new design is implemented.

This initial assumption—that simplifying the payment process will improve booking completion—is a plausible hypothesis that can guide your design changes but requires testing to confirm.

What could go wrong with jumping to a solution?

When you jump from a solution straight into execution.

Jumping to a solution isn’t about rushing to get your project done and dusted.

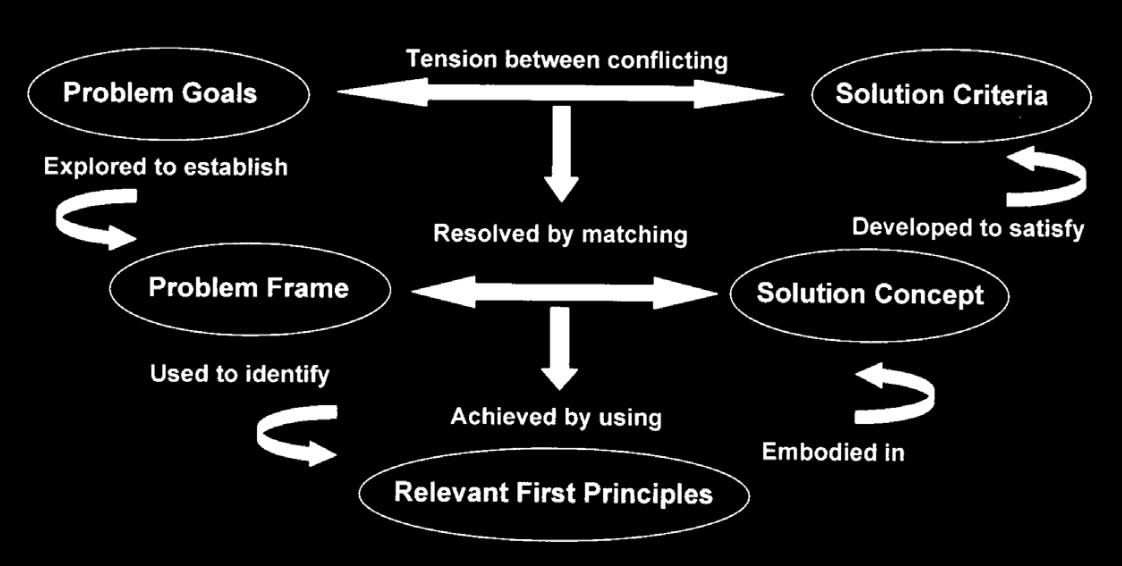

As Nigel Cross suggests in his diagram, the process is non-linear and works concurrently between defining the problem and developing the solution.

As we perceive the relationship between problem and solution like in the diagram, jumping to a solution is simply part of the process—not a sign of ignorance.

You’ll continually reflect on the problem along the way. It’s a two-way street where you move back and forth between framing the problem and refining the solution.

An invitation to reflect: When you feel you are jumping to a solution, ask yourself these questions:

How do I understand the problem?

What's the core issue I'm really trying to solve, and what basic truths underlie it?

How do I make sense of the best possible explanation (plausible hypothesis)?

Next time, don’t feel guilty for instinctively having your head full of ideas.

Embrace it.

Remember, having a solution is an opportunity to frame the problem more clearly, explore the tension, form a plausible hypothesis, and move forward with purpose.

Your design buddy,

Thomas

How much did this week’s reading resonate with you? I’d love to hear your thoughts!

Feel free to share any reflections or insights in the comments below.

Also, show your support by clicking the heart button ❤️ or sharing this with a friend, colleague, or fellow designer!