AI companies never sleep, I guess? They’re racing each other, even it’s a marathon toward building AI that can match or surpass human capabilities, or what they call AGI.

The internet’s been flooded with Ghibli-fied artwork, thanks to the new ChatGPT 4o ‘create image’ feature1.

This update is a massive step up from the previous version, DALL·E 32, in so many ways. I’m especially blown away by how well it handles text3.

But beyond all the improvements, the internet is once again split, full of awe, concerns, praise, and worries… all at once. Some people are enjoying their Ghibli-fied photos, while others are calling it out4. OpenAI, on the other hand, seems to be enjoying the spotlight, adding a million new users in just a few days5. Even their CEO changed his profile picture to a Ghibli-style artwork on X.6

So what is for Studio Ghibli? Aside from perhaps feeling robbed (?) although there’s no official statement yet other than a fake legal warning notice7. The creator firmly stated back in 2016 that using AI is an insult to life itself8. I’m wondering what they’re thinking in the midst of this situation.

Sure, Ghibli's getting publicity, similar to when McDonald's featured Minecraft toys in Happy Meals. My kids suddenly wanted those again after ages. McDonald's made sales, Minecraft got exposure, it’s collaborative. But is what's happening now with AI and Ghibli collaborative or exploitative?

I don’t want to go deep into that here, but it’s a good reminder: there’s always two sides to a coin.

That’s been my position with AI.

I’m constantly in tension, loving it, yet worrying about what’s ahead.

If you feel this too, subscribe and join me in exploring how we, as digital product designers (UX/UI), can preserve human agencies in an AI-driven world.

Why design still matters?

Reflecting on Studio Ghibli made me ask: what is the true value of creation?

AI can now generate artwork in seconds with just a prompt.9. Sure, it’s not perfect, but it’s evolving fast. As creation speeds up and cost drops, so can our sense of value.

But does that make Ghibli’s work any less valuable?

I don’t think so.

Take a 4-second scene from The Wind Rises (2013). At first glance, it looks ordinary.

But animator Eiji Yamamori spent 15 months crafting it. In the documentary, Miyazaki walks up to him and says, “It was worth it.” I nearly teared up.10

Studio Ghibli is known for sticking to traditional animation. Every frame is carefully hand-drawn by their animators. I’m not even a hardcore fan. I’ve just seen Totoro and Spirited Away. But I’d never thought about what happens behind the scenes.

Now, I can’t watch their films the same way. Knowing the care and effort behind every second changes everything.

It gives their work a different kind of meaning.

That reminded me of something John Maeda, VP of Engineering for AI at Microsoft, shared not so long ago11:

I find that with AI it’s easy to make many pretty things that have minimal value. And it’s still difficult to make what is beautiful — that which holds real value.

Pretty, but empty

Try generating a UI screen with AI. The first version might look great at first glance.

My question is, even if your prompt was crafted with clear intent, does it truly reflect the context of your project, your goals, and the constraints you're working within?

I doubt it.

Have you ever designed something and nailed it on the first draft?

The truth is, design is messy. You face a lot of unknowns and have to make choices without having all the answers. You try things, change direction, and keep improving as you go. That’s how we align with the context, get clearer on the intention, and work within the constraints, so in the end, everything fits the users you’re designing for.

That’s what gives a design artifact meaning, connecting what you make to human needs and use. And those iterations and explorations you go through? They are acts of meaning-making, just like Klaus Krippendorff (1932–2022), the communication scholar, designer, and cyberneticist, described.12

Here’s something even more interesting: design and meaning have always been connected, they share similar roots.

Meaning comes from roots like mænan — to intend, to signify, to indicate.13

Design from designare — to mark, to indicate, to point something out with purpose.14

The act of meaning-making doesn’t happen just by prompting AI.

Prompting is an action, like dragging a rectangle or adding text with a tool, just 10x faster.

What you prompt might be pretty, but it’s empty. It’s just a first draft—a placeholder.

How to make meaning

Making meaning isn’t a standalone process. It’s deeply tied to how you make sense of everything around you—the problem space you’re designing for, your users, your business goals, and the constraints you’re working within.

Sense-making helps you navigate complexity. It’s about understanding the context, clarifying your intention, and working within constraints.15

You take all of that and turn it into something that has meaning—through the screens you design, the flows you create, and the way you structure information.

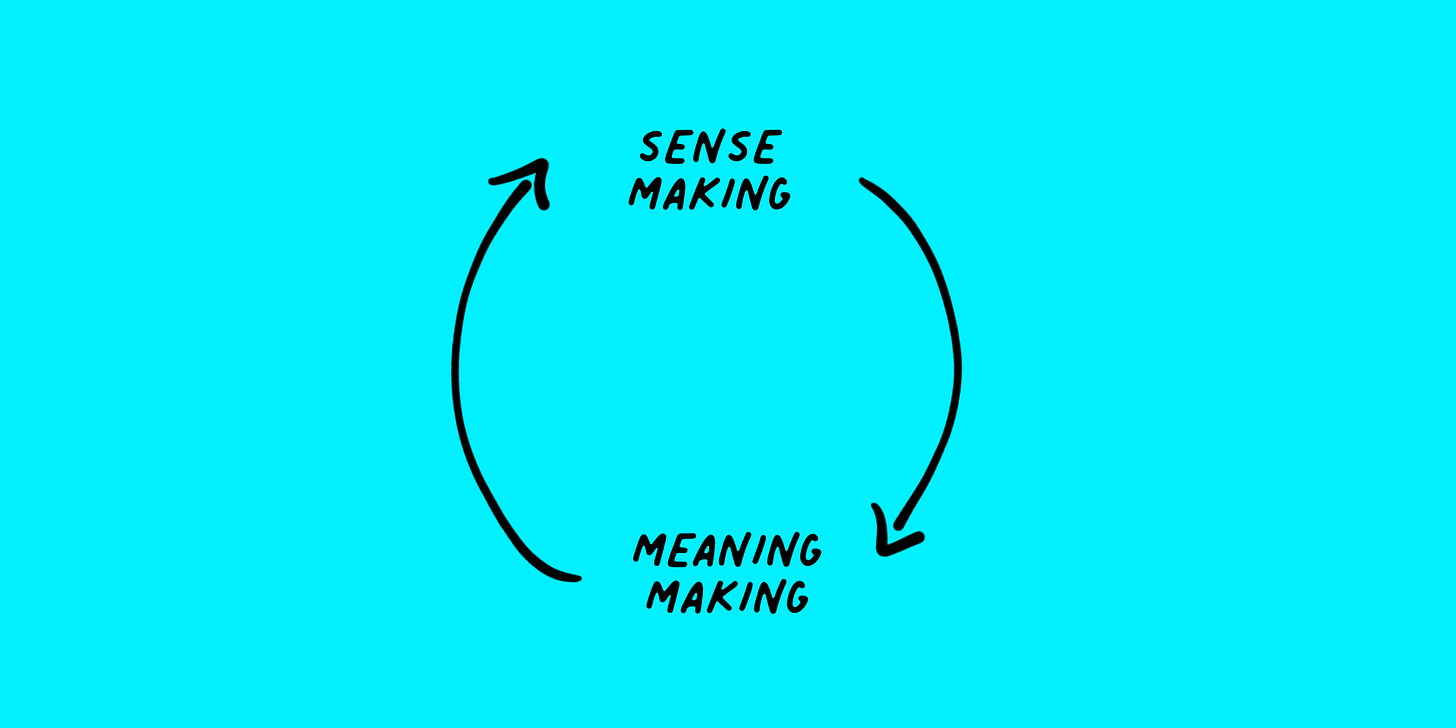

Although I draw it as a cycle, I like to think of sense-making and meaning-making as a dance.

Sometimes the rhythm is fast—like during prototyping, when you’re quickly making sense and creating meaning. Other times, it’s slower. You gather feedback, check analytics, and take your time to reflect and adjust.

In both cases, you’re working with three key threads: context, intention, and constraints. These are what guide the process. You’re always interpreting them, aligning them, and moving between sense-making and meaning-making.

Context: Primarily about users and the business. On the user side, it’s understanding behaviors, needs, pain points, and motivations. On the business side, it’s goals, metrics, priorities, and strategy. Context can also include things like culture, environment, tech trends, or system-level factors that affect the problem space.

Intention: The reason behind what you’re building. It could be to drive adoption, improve retention, simplify a task, or encourage behavior change. Intention shows the purpose behind design choices and the impact you want to make for both users and the business.

Constraints: The limits you need to work within, like tech, time, resources, or ethics. They’re not just obstacles, they help frame the problem and sharpen the focus of your solution.

Pretty with Intentionality

It’s easy to design something when you ignore the context, have no clear “why,” and disregard the constraints.

But when you truly understand the user and the business (context), get clear on the why behind your decisions (intention), and have to work within real-world limits (constraints)—that’s when design gets challenging.

Think about the last time…

You tried to fit something clean and compact above the fold and two teams had competing interests.

Or when you had to simplify a flow that needed to work for both first-time users and returning users.

Or when every team wanted their feature in the nav, and you had to make it feel effortless and intuitive.

Or when you tried to follow accessibility guidelines, but the brand team pushed for soft grays and subtle contrasts.

Or when your layout worked great in English, until localization stretched every label and broke it.

Those hurdles—that’s where design becomes the act of meaning-making.

Living out designare: to mark, to indicate, to point something out with purpose.

That’s where craft and judgment matter most—wrapping context, intention, and constraints into every decision, while still making it look good.

From pretty but empty to pretty with intention.

Making meaning is human domain

It belong to us.

Only we can truly make sense of complexity, make judgments, and hold nuance.

AI can augment our work—it can be a multiplier.16

Let it take care of some of our tasks and give us back what matters most: time.

Time to think better, design with more intention, and create work that’s truly meaningful.

Time is something we humans value more than anything else on earth. Which for AI has no meaning … which is why beauty will remain reserved as a particularly human pursuit.

It’s about the intrinsic weight of the value of time ascribed to our very finite lifetimes.

Because AI can't value what it cannot fully experience: time itself. Ironically, it’s always running on a CPU clock.

– John Maeda, VP of Engineering for AI at Microsoft

Until next one,

Thomas

Thanks for reading Design Buddy. Show your support by hitting the ❤️ or sharing this with a friend, colleague, or fellow designer. It helps spread the word and reach more people. Big thanks!

If you’re enjoying the publication, the best way to support it is by making a pledge. Your support helps keep all posts free, so they can continue reaching and helping more designers.